Monitoring Impacts of White-Nose Syndrome (WNS): Decline and Stabilization in a Little Brown Bat Nursery Colony,

A Case History from New York

A New York nursery colony of little brown myotis (Myotis lucifugus) offers a window of opportunity for monitoring the impact and hoped for recovery of this recently devastated species. The colony occupies seven four-chamber, nursery-style bat houses provided by Lew and Dorothy Barnes. The houses were mounted on two sides of their barn near Lake Erie in western New York in the spring of 1995. By July 16, 1997 they had attracted 1,075 little brown myotis. Often aided by professional biologists, regular emergence counts were made between 1997 and 2013, providing potentially invaluable baseline data on WNS-induced population impacts.

Exemplary of the importance of timing, just 707 bats emerged on July 19, 2007, while the count rose to 1,624 by July 24. That difference was undoubtedly heavily influenced by newly flying young. Learning from experience, subsequent counts were made in late July or August.

From 2002 through 2004 mid-August counts held steady between 1,597 and 1,645. On August 21, 2005 numbers had declined to 1,147, but rose to 1,321 by August 27, 2008. At the next count, on August 19, 2010, four years after the discovery of WNS in New York, the colony still numbered at least 991, and surprisingly was back to 1,296 by July 20, 2012. This fluctuation may have been, in part, due to the tendency of many bats to move into a wider variety of roosts following the fledging of young. The most consistent year-to-year results come from monitoring the adults after young are born, but before they are ready to fly. Where feasible, it is best to compare a photographic count of roosting bats with an emergence count that evening.

Few, if any, bats should be handled at any site relied on for monitoring status trends, since growing numbers may leave for alternate roosts, just to avoid the handling. Such behavior results in false indication of decline.

Protected bat house colonies, once well established, provide ideal opportunities for monitoring. Such bats are normally quite tolerant of being slowly and quietly approached to within six feet with a dim, preferably rheostat-controlled light. From that distance a camera and flashes can be aimed directly up into the roost for a quick focus and a couple of photos without undue disturbance (or casting shadows that obscure the bats).

Daytime photo counts can be compared with emergence counts that evening. The latter will tend to be slightly higher, because a few bats are often hidden from view in photos. Two to three well-timed bat house counts per site, each summer, may provide useful baseline data to which ultrasonic monitoring in summer habitat can be compared.

In the case of the Barne’s bat house colony, it would be hard to miss the extent or timing of the WNS die-off. Though the apparent drop in 2010 could have resulted from earlier dispersal to alternate roosts that year, the precipitous drop from 1,296 in 2012 to just 453 in 2013, down to 52 in 2014 is clear, and visual counts of roosting bats have remained between 50 and 70 ever since.

Unfortunately, the failure of biologists to return after the summer of 2013, has left a gap in consistently timed, standardized emergence counts. Nevertheless, it is clear that losses reached or exceeded 90 percent.

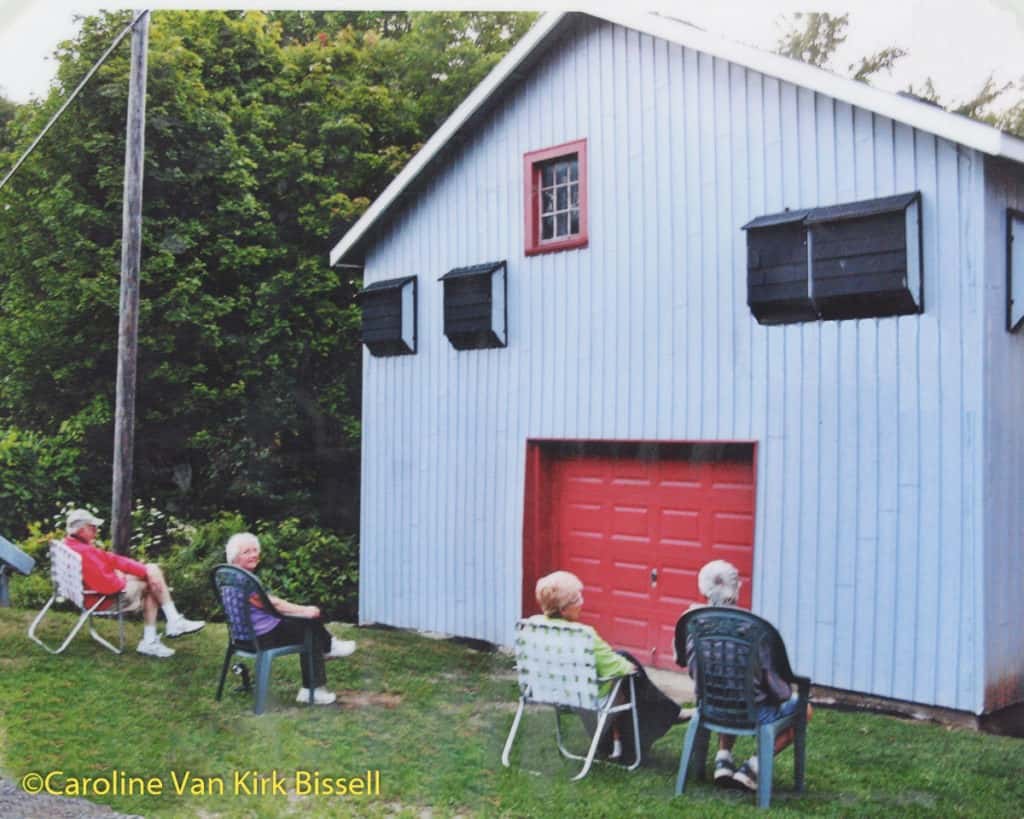

On August 28, 2016, I was able to join two of our members, biologist Jonathan Townsend and Chautauqua “Bat Chat” presenter, Caroline Van Kirk Bissell, in a personal daytime investigation of the Barne’s bats. Thanks to their efforts, we hope, once again, to have reliable emergence and photographic counts, beginning in 2017, hopefully in time to begin documenting gradual recovery of resistant individuals.

Though biologists have counted surviving bats in hibernation caves, it appears that some valuable opportunities to monitor nursery colonies, especially the most reliably countable ones in bat houses have been neglected. This is especially unfortunate, given that nursery colony emergence counts can be made without adding further stress to already threatened bats. Bats under attack by the WNS-causing fungus (Pseudogymnoascus destructans) are forced to waste limited fat reserves, resulting in starvation before spring.

When roosts are disturbed in winter, no matter how briefly or how good the intentions, each disturbance causes bats to at least partially arouse, costing additional loss of fat reserves in what for some undoubtedly becomes the proverbial straw that broke the camel’s back.

As seen in our recent New York observations, WNS has brought some of America’s once most abundant cave-hibernating bat species to the very brink of extinction. Let’s not put them at further risk by needless disturbance during hibernation. Where available, occupied bat houses may prove exceptionally useful in alternative monitoring.