The Costs of Bat Decline

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

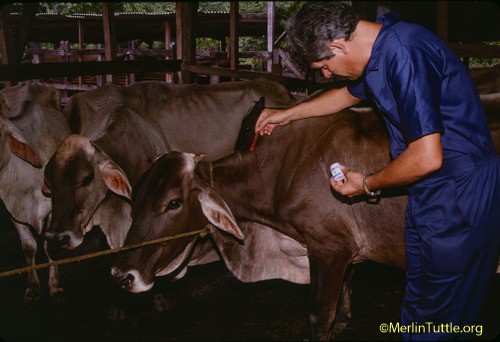

The Wildlife Disease Association hosted a panel discussion on vampire bats (Desmodus rotundus), their impact, status, and changing distribution on August 5, 2018. A panel of six speakers from Europe, Mexico, and the U.S. were invited to speak. In the lead-off, tone-setting presentation, I outlined the global value of bats, with special emphasis on Latin America, then proceeded to discuss my decades of observations on vampire control and the enormous damage done when beneficial species are inadvertently targeted. I favored control limited to the vampires causing problems. However, I emphasized that vampire problems are two-fold. One of course involves feeding on livestock and occasionally humans. The other involves their potential impact in crowding other species out of already declining roosting options. The dramatic expansion of vampire populations due to livestock introduction is likely impacting many other bat species that are essential to healthy ecosystems.

During my early bat surveys in remote rain forests inhabited only by aboriginal Indians, I rarely encountered vampire bats. In fact, I do not recall ever having seen a Yanomamo Indian bitten, despite their habit of sleeping nude in lean-to shelters without mosquito nets. I first encountered significant numbers of vampire bats where Indians under European influence were keeping chickens, pigs, or other livestock. My anecdotal observations indicated that humans first became substantial targets when they began keeping pigs or chickens. Vampires became accustomed to feeding on these, and when they were slaughtered for feasts, the hungry bats turned to humans. Later when ranchers sold livestock, again suddenly reducing the food supply, vampires whose numbers had grown to depend on their herds, turned to people.

Only three species of vampires exist. All live only in Latin America, and only one, the common vampire, poses a significant threat to human interests. More than 350 other species are highly beneficial, keeping insect populations in check, pollinating flowers, and dispersing seeds.

I noted that, even the common vampire is of potentially great medical value. Its saliva reportedly is a veritable treasure trove of unique regulatory molecules of potential value in developing modern medicines. I personally like vampire bats. They are exceptionally intelligent and sophisticated and even can be affectionate to humans. I hate to see them killed. However, I believe that some control is necessary.

Even if vaccines already being tested prove effective in eliminating vampire born rabies, a periodically significant threat to cattle ranching, governments have little incentive to extend such service to frontier campesinos who pose the greatest threat to beneficial species. Most have at least a few pigs, chickens, or a horse, and when vampires begin biting their livestock or families, they understandably declare war on bats in general. They often have no idea that most are beneficial, even essential to their best interests. By the time ranching and greater government assistance arrives, the most important bat roosts, especially caves with large colonies, have already been destroyed.

A lively discussion followed the six presentations. All agreed that traditional control has failed, causing more harm than good. Today, there are more vampires than ever, while huge populations of highly beneficial species have been mistakenly destroyed. Sustained efforts to educate and assist poor frontiersmen, not just established ranchers, are much needed.

Grossly exaggerated media stories only add to existing problems and likely will pose additionally significant threats if vampires continue their northward advance due to climate change.

They are already common not far south of the U.S. border in Mexico and likely will be found crossing into Texas in decades to come. They would be easily controlled if permitted. However, existing wildlife legislation could protect vampires and might take years of controversy to suitably amend. Should that occur, their arrival could be exploited by sensational media stories doing great harm to conservation. Substantial discussion focused on that very real possibility.

Love our content? Support us by sharing it!

Can we afford to lose bats? A recent study by Eyal Frank of the University of Chicago reveals that the dramatic decline in U.S. bat

Bats are among the most fascinating yet misunderstood creatures in the natural world, and for many conservationists, a single experience can ignite a lifelong passion

Many bat conservationists know that Kasanka National Park in Zambia is an exceptional place for bats, but it is also the place that sparked my

The Kasanka Trust is a non-profit charitable institution, which secures the future of biodiversity in Kasanka National Park in Zambia. They welcome internships for students

2024 © Merlin Tuttle’s Bat Conservation. All rights reserved.

Madelline Mathis has a degree in environmental studies from Rollins College and a passion for wildlife conservation. She is an outstanding nature photographer who has worked extensively with Merlin and other MTBC staff studying and photographing bats in Mozambique, Cuba, Costa Rica, and Texas. Following college graduation, she was employed as an environmental specialist for the Florida Department of Environmental Protection. She subsequently founded the Florida chapter of the International DarkSky Association and currently serves on the board of DarkSky Texas. She also serves on the board of Houston Wilderness and was appointed to the Austin Water Resource Community Planning Task Force.

Michael Lazari Karapetian has over twenty years of investment management experience. He has a degree in business management, is a certified NBA agent, and gained early experience as a money manager for the Bank of America where he established model portfolios for high-net-worth clients. In 2003 he founded Lazari Capital Management, Inc. and Lazari Asset Management, Inc. He is President and CIO of both and manages over a half a billion in assets. In his personal time he champions philanthropic causes. He serves on the board of Moravian College and has a strong affinity for wildlife, both funding and volunteering on behalf of endangered species.